Muscle Knots & Myofascial Trigger Points

What Are They, Cause, Physiology & Treatment Options

A regularly asked question is "what are (muscle) knots?", closely followed by "what causes them and how can they be avoided?".

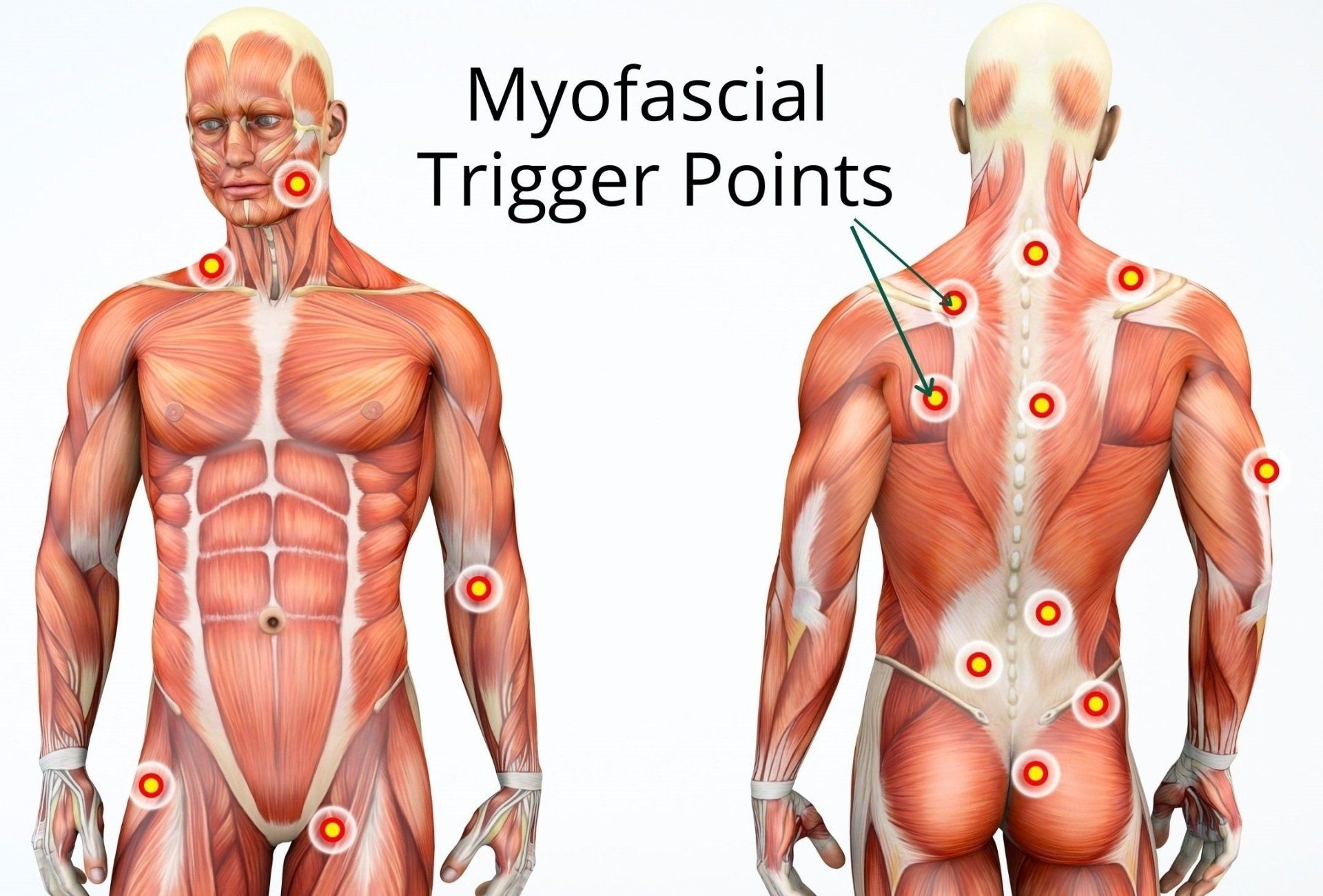

A simple short answer is; muscle knots are small, nodule-like, hypersensitive areas which can be painful to touch and are mainly caused by overuse, stretched muscle from frequent and repetitive strain and especially caused by poor posture.

The medical term for muscle knots is myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) which occur when muscle fibres or bands of fascia tense and tighten (2).Trigger points are classified as either 'active' or 'latent'. Active trigger points are tender, spontaneously painful and refer to trigger points that do not necessarily need to be touched for them to be painful (7). This contrasts to latent trigger points which are only painful when somebody presses on the sensitive area, they may be associated with restricted ranges of movement and tenderness is not associated with spontaneous complaints of pain (7).

Xiaoqiang et al.,

(2014) describe MTrPs as hyperirritable regions located within muscle, fascia, or

tendinous insertions, where local pain is perceived

as a deep and aching palpable taut band with referred pain in

the same or a distant position and local twitch responses

(LTRs) may be felt during forceful palpation and/or via (acupuncture) needling.

Myofascial trigger points can cause pain and affect joint range of motion which is why individuals with hypersensitive trigger points should aim to treat them as early as possible.

Myofascial Pain Syndrome

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is one of the most common chronic pain syndromes and often overlooked as a source of muscle pain, discomfort, and dysfunction. Myofascial pain often arises in postural related skeletal muscle which may refer to other areas of the body (3). Examples of postural tonic

muscles may include deep back erector spinae muscles, gluteal (buttocks), and cervical (neck) muscles which seem to be involved more often than

others(3).

Painful muscles surrounding connective tissue may either be described as being 'acute' with lasting less than 6 weeks or 'chronic' by lasting more than 3 to 6 month and be caused by the development of myofascial

trigger points in muscle (MTrPs) (1).

Various individuals in all types of populations may suffer from myofascial pain, especially those who participate in sport, carry out a physically demanding trade or those who experience age related degeneration (7).Various traumas, such as contusions, sprains, and strains,

may induce acute myofascial trigger points with their onset possibly initiated by repetitive micro-injuries, including overload and overuse of muscle which can often lead to chronic myofascial trigger points (7).

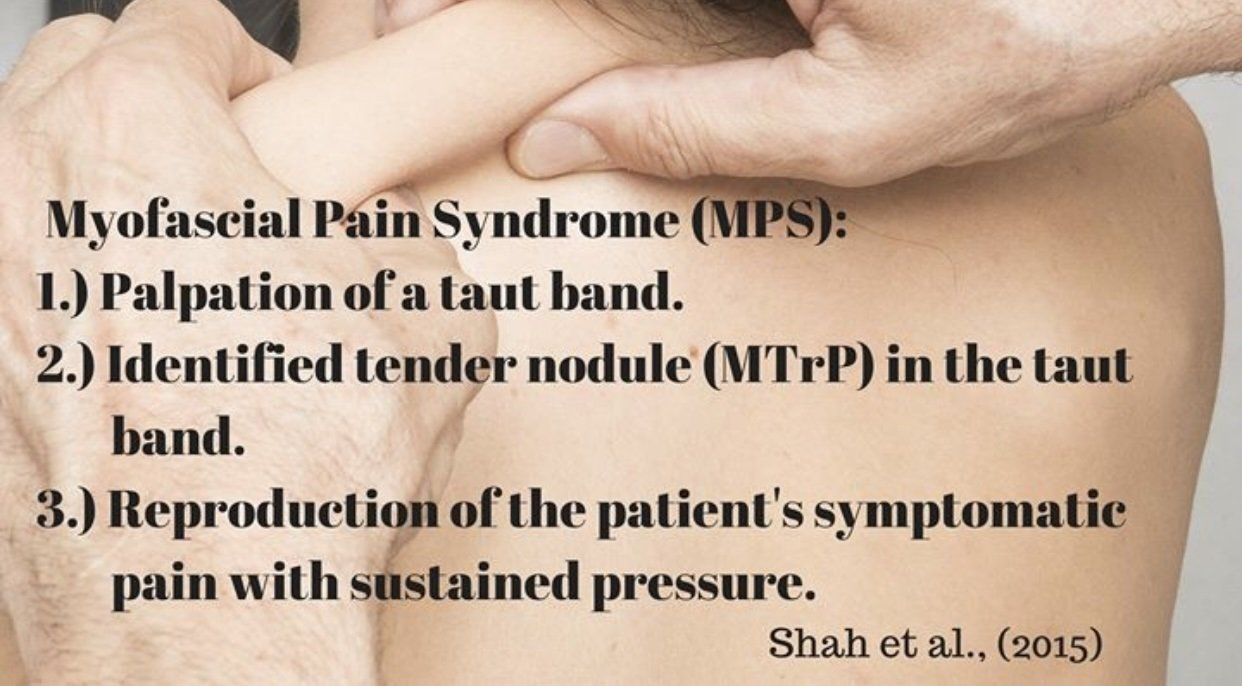

The current gold standard for the diagnosis of MPS is the physical examination as described in The Trigger Point Manual (5) (Figure 2):

- Palpation of a taut band; Diagnosis of MPS has been tissue specific and anatomically based on palpation of the skeletal muscle for MTrPs.

- Identification of an exquisitely tender nodule (MTrP) in the taut band.

- Reproduction of the patient's symptomatic pain with sustained pressure.

History of MPS as a Diagnosis

The discovery of myofascial trigger points and muscle knots can date back to Guillaume de Baillous (1538-1616) of France who was one of the first to write in detail about muscle pain disorders. In 1816, the British physician Balfour associated “thickenings” and “nodular tumors” in muscle with local and regional muscle pain (5). In 1843, Froriep coined the term “muskelshwiele” (muscle callouses) to describe what he believed was a “callus” of deposited connective tissue in patients with rheumatic disorders (5).

In 1904, Gowers suggested that inflammation of fibrous tissue (i.e., “fibrositis”) created the hard nodules and Schade (1919) later proposed that the nodules should be termed as “myogeloses” (5). In the mid 1900s, important work was conducted independently by Michael Gutstein in Germany, Michael Kelly in Australia, and J.H. Kellgren in Britain. By injecting hypertonic saline into various anatomical structures such as fascia, tendon, and muscle in healthy volunteers, Kellgren was able to chart zones of referred pain in neighbouring and distant tissue (5).

The U.S. physician Janet Travell, whose work on myofascial pain, dysfunction, and trigger points is arguably the most comprehensive to date. Travell and Rinzler invented the term “myofascial trigger point” in the 1950s after understanding that nodules can be present and refer regional pain to both muscle and overlying fascia accompanied by increased muscle tension and reduced joint flexibility (5).

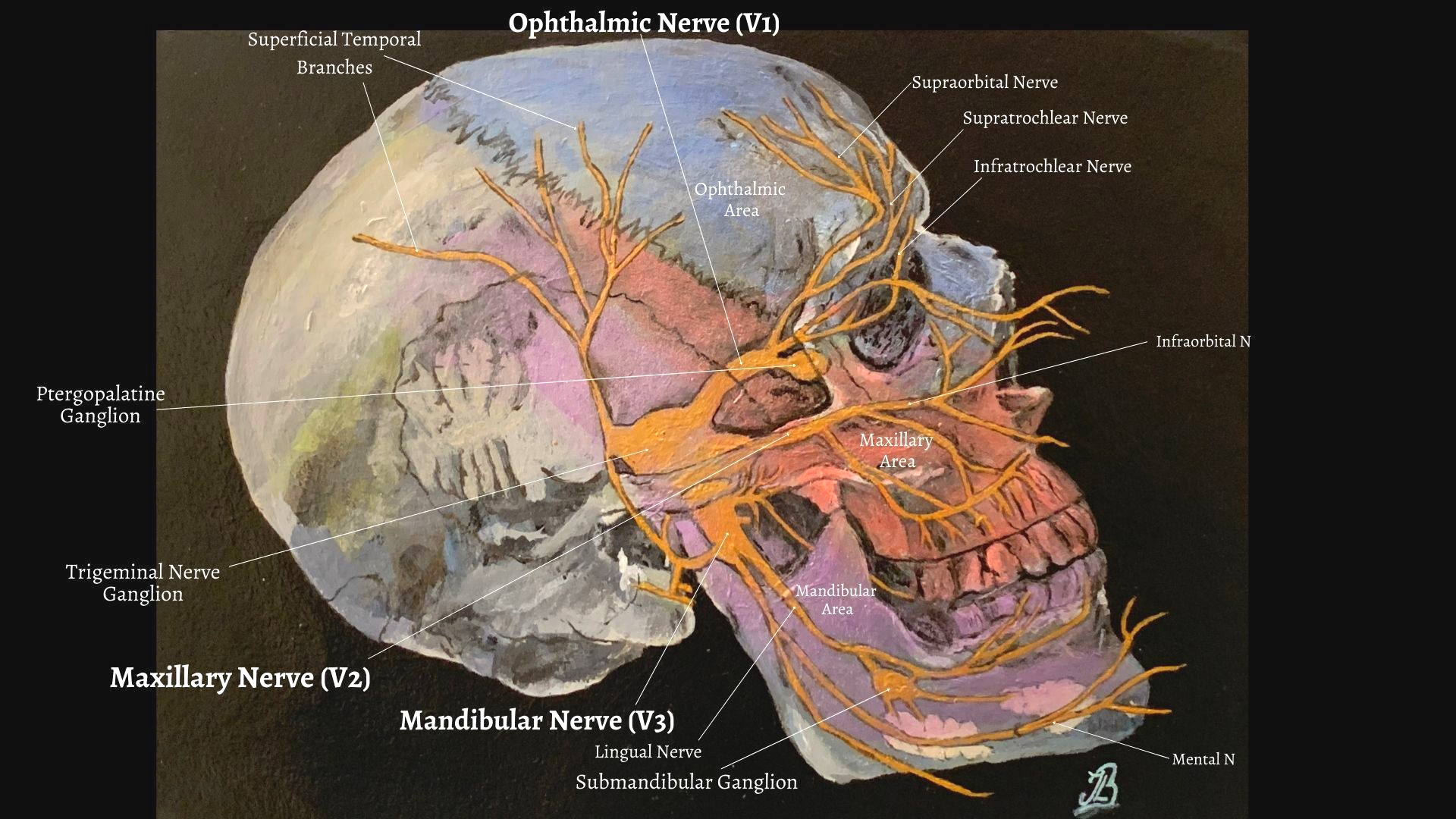

MPS has also been associated with other pain conditions including radiculopathies, joint dysfunction, disc pathology, tendonitis, craniomandibular (jaw) dysfunction, migraines, tension type headaches, carpal tunnel syndrome, computer-related disorders, whiplash-associated disorders, spinal dysfunction, pelvic pain and other urologic syndromes, post-herpetic neuralgia, and complex regional pain syndrome (5, 6).

MPS Is Different To Fibromyalgia

MPS is known to coincide with other diseases and syndromes associated with pain, e.g. rheumatic diseases and fibromyalgia.However, fibromyalgia differs with it being a widespread and symmetrically-distributed pain condition associated with sleep and mood disturbances.

The pain of MPS is usually local or regional and may be found in a limited number of select quadrants of the body

and are thought to present independently of mood or sleep abnormalities with recent studies indicating that MPS is associated with both mood and sleep disruptions (5).

The definition and pathogenesis of MPS, however, is still not fully understood and disagreement still persists as to whether MPS is a disease or process rather than a syndrome.

The Role of Muscle and The Cinderella Hyposthesis

The Cinderella Fibre Hypothesis was first proposed by Hagg (1990) which explains how low level muscle damage can happen via low-threshold motor units (MUs) within muscles which are continuously activated during low level static exertions (LLSEs) (3, 7). Types of LLSEs or exertions are typically utilized by occupational groups such as

office workers, musicians, hair dressers and dentists.

These "Cinderella" fibers are small low threshold muscle fibres which can become continuously overloaded and more prone to develop into myofascial trigger points as they are activated for longer and are more likely to be metabolically exhausted before other fibres. A study by Treaster et al.

(2006) supports the Cinderella Hypothesis by demonstraeting that low-level, continuous muscle contractions such as the upper trapezius muscles within office workers during 30 minutes of typing induced formation of MTrPs. These muscle fibres contrast to larger motor muscle fibres which do not work as hard and spend less time being activated.

The "Cinderella" fibre theory is of interest to know, however, it does fail to explain all aspects of injury related to LLSEs and although low-threshold muscle fibres may fatigue and become metabolically exhausted, this does not explain how the muscle pain occurs (6).

The Energy (ATP) Deficit Hypothesis

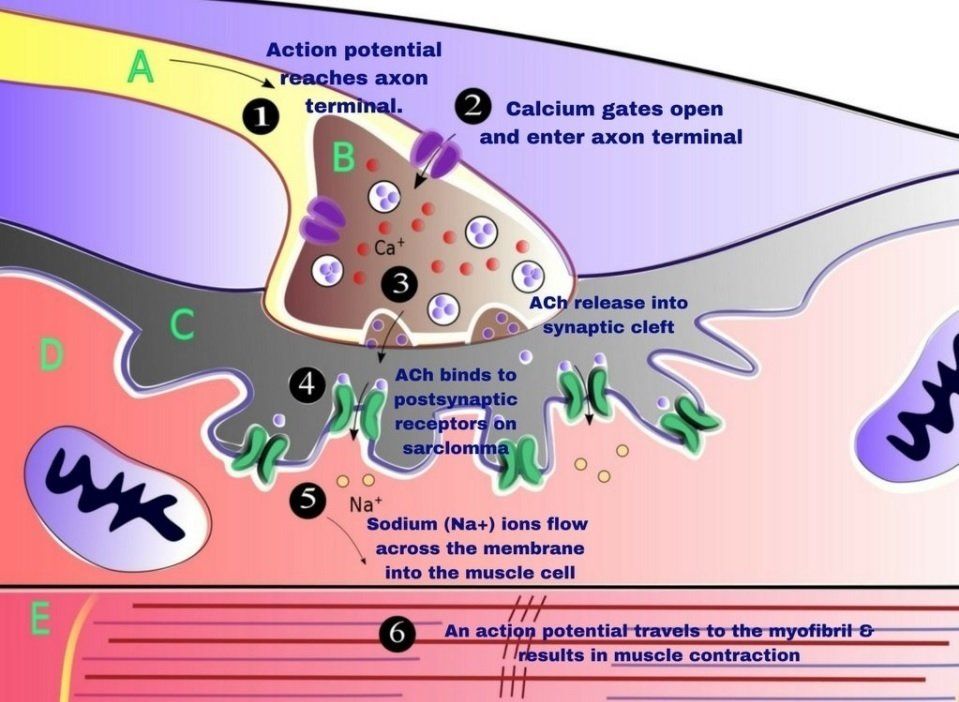

A widely

accepted hypothesis for the pathophysiology of myofascial pain is the energy crisis hypothesis. Trigger points may develop because some initiating events or activity causes an excessive release of acetylocholine (ACh) from the motor endplates resulting

in increased fibre tension and localised ischemia which restricts the blood flow and creates insufficient ATP synthesis needed to restore energy (3, 7).

The increased demand and reduced supply of ATP forms the energy crisis and encourages the release of neuroreactive substances and metabolic byproducts (i.e., bradykinin (BK), substance P (SP), serotonin (5-HT)) which causes the peripheral nociceptors (pain receptors) to become sensitive (3).

The increased demand and reduced supply of ATP forms the energy crisis and encourages the release of neuroreactive substances and metabolic byproducts (i.e. bradykinin (BK), substance P (SP), serotonin (5-HT)) resulting to peripheral nociceptors to become sensitive (3, 7).Without ATP, the sarcoplasmic reticulum does not function correctly and the muscle sarcomeres remain contracted as the lack of energy (ATP) means that the the actin and myosin cross-bridges cannot disengage or release (5).

ATP is also needed by the calcium (Ca2+) pump to remove calcium (Ca2+) from the muscle binding sites and restore them to the

sarcoplasmic reticulum to the myoplasm which leads to the activation of the actin-myosin contractile system (3). This happens as Calcium (Ca2+) binds to troponin on the muscle which makes the muscle fibres contract.Localised areas containing "contraction knots" are believed to release sensitizing

agents and additional acetylcholine (ACh) that cycles back to cause increased fibre

tension.A feedback loop to maintain contraction is created and a self perpetuating

cycle is established.Until this positive-feedback loop is

interrupted, the muscle sarcomeres at the TrP remain in a shortened state and creates a local energy crisis.

Critique to the Energy Deficit Theory

There is no explanation for the initiating event that causes the excessive release of ACh to occur in the first place and this theory also assumes that the motor endplates are the focus of attention for trigger point development.

- There is no evidence suggesting that the endplates are responsible for trigger point development.

- This theory fails to explain why MTrPs are more prevalent at certain 15 muscle locations than others (5).

Muscle Overuse and What Happens When Hyaluronic Acid (HA) Levels Rise

Hyaluronic acid (HA) functions as a lubricant and HELPS muscle fibres to glide between each other without friction.Muscle overuse or traumatic injury can cause the sliding layers start producing immense amounts of HA which then aggregates into supermolecular structures changing both its configuration, viscoelasticity and viscosity (2, 5).

Due to its increased viscosity, HA can no longer function as an effective lubricant and instead increases resistance in the sliding layers and leads to densification of fascia or abnormal sliding of muscle fibres (2, 5). An interference with sliding can impact range of motion and cause difficulty with movement, including quality of movement and stiffness. In addition, under abnormal conditions, the friction results in increased neural hyperstimulation (irritation), which then hypersensitizes mechanoreceptors and nociceptors embedded within the fascia (2, 5). This hypersensitization correlates with a patient's experience of pain, allodynia, paresthesia, abnormal proprioception, and altered movement.

Treatment for Myofascial Trigger Points (MTrPs)

Treatment for myofascial trigger points mainly aims to inactivate the trigger points by reducing muscle tone, correct biomechanical imbalances or defaults which may maintain local muscle tensions (7). Different treatment approaches might be considered for the management of MTrPs including the following:

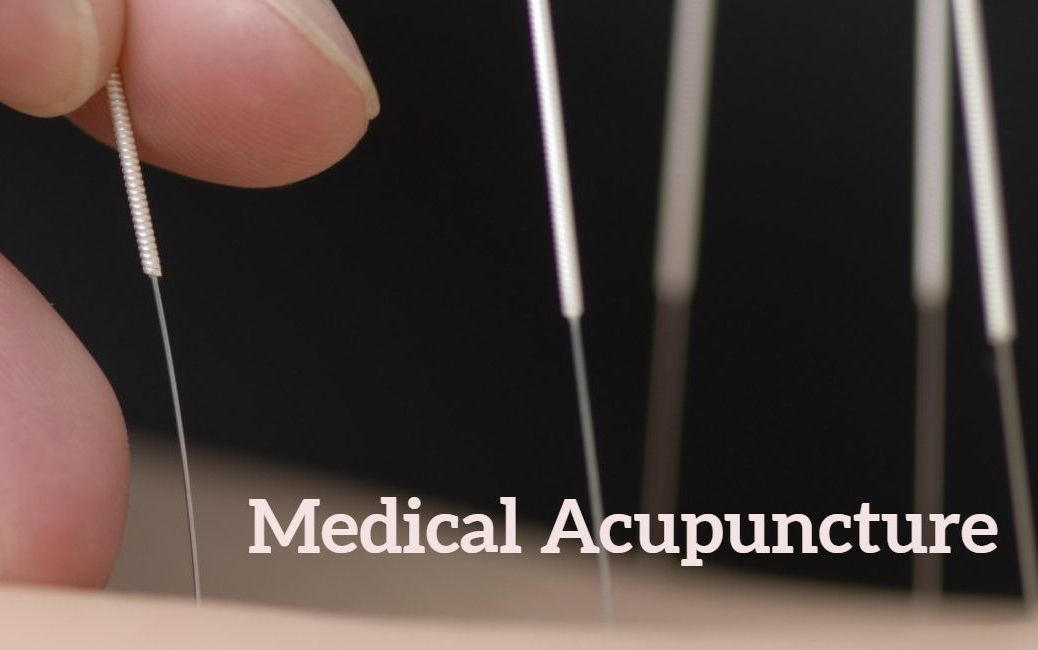

Dry Needling or Medical Acupuncture

Myofascial trigger points might be punctured using acupuncture needles and create local twicth response (LTR).

Massage and Hand Manipulation

Physically locating the MTrPs and apply various massage skills.

Stretches and Home Exercises

Either performed via self stretching or passive stretching techniques performed by the therapist. Postural and strength exercises might also be prescribed to help correct muscle imbalances. Exercises also aim to restore muscle length and flexibility along with strengthening and stabilisation (7).

Osteopathic Spinal and Peripheral Joint Manipulations

Osteopathic manipulations might be applied with the aim to reduce the tension within the local tendons and muscle attachments and reduce stiffness within the joints. One example of a manipulation techniques can be viewed in the below applied for the neck.

References

1. Hoyle, J. (2006) EFFECTS OF POSTURAL AND VISUAL STRESSORS ON TRIGGER POINT DEVELOPMENT, MUSCLE ACTIVITY, BLINK RATE, AND DISCOMFORT DURING COMPUTER WORK

, Ohio University, MSC.

2. Marieb, Elaine Nicpon; Hoehn, Katja (2007). Human anatomy & physiology

. Pearson Education. p. 133. ISBN

978-0-321-37294-9.

3. Minerbi, A., Vulfsons, S. (2018) Challenging the Cinderella

Hypothesis: A New Model for the Role

of the Motor Unit Recruitment Pattern

in the Pathogenesis of Myofascial Pain

Syndrome in Postural Muscles

,Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal, 9; 3: 1-8.

4. Nall, R. (2020) How To Treat Muscle Knots, Medical News Today; [online] https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321224#_noHeaderPrefixedContent

, last viewed 24/11/2020.

5. Shah, J.P., Thaker, N., Heimur, J., et al. (2015) Myofascial Trigger Points Then & Now: A Historical and Scientific Perpective. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,

7:746-61.

6. Treaster, D., Marras, W. S., Burr, D., Sheedy, J. E., Hart, D. (2006) Myofascial Trigger Point Development From Visual and Postural Stressors During Computer Work.

J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Apr;16 (2)

:115–124.

7. Xiaoqiang, Z., Shusheng, T.,Qiangmin, H. (2014) Understanding of Myofascial Trigger Points

, Chinese Medical Journal, 127; 24: 1-7.