Sacroiliac Joint and Lower Back Pain

Common Pain Presentations, Cause and Treatment Options

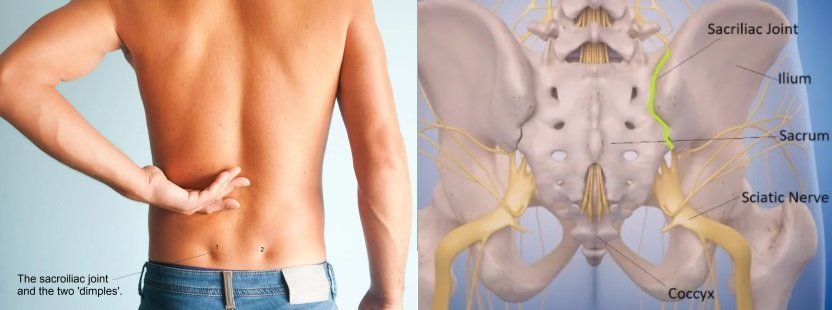

Pain felt near or around the the two dimples within the lower back might indicate sacroiliac joint (SIJ) related pain.Injuries to the sacroiliac joint can occur from various etiologies with most cases of SI joint injury caused via either repetitive microtrauma or acute trauma (11).

There are two sacroiliac joints in the body which are located between the iliac bones and the sacrum. They connect the spine to the hips and help provide a major role for support, stability and shock absorption during impact whilst walking and lifting.

SIJ pain is commonly an underappreciated but a common cause of chronic lower back pain (LBP) and pelvic girdle pain (PGP). Various different presentations of related pain can make a diagnosis challenging, but understanding the condition's anatomy, clinical presentation and methods for assessment is important to make an accurate diagnosis, determine the source of painand increase the likelihood of optimising a successful and faster recovery (2).

Anatomy

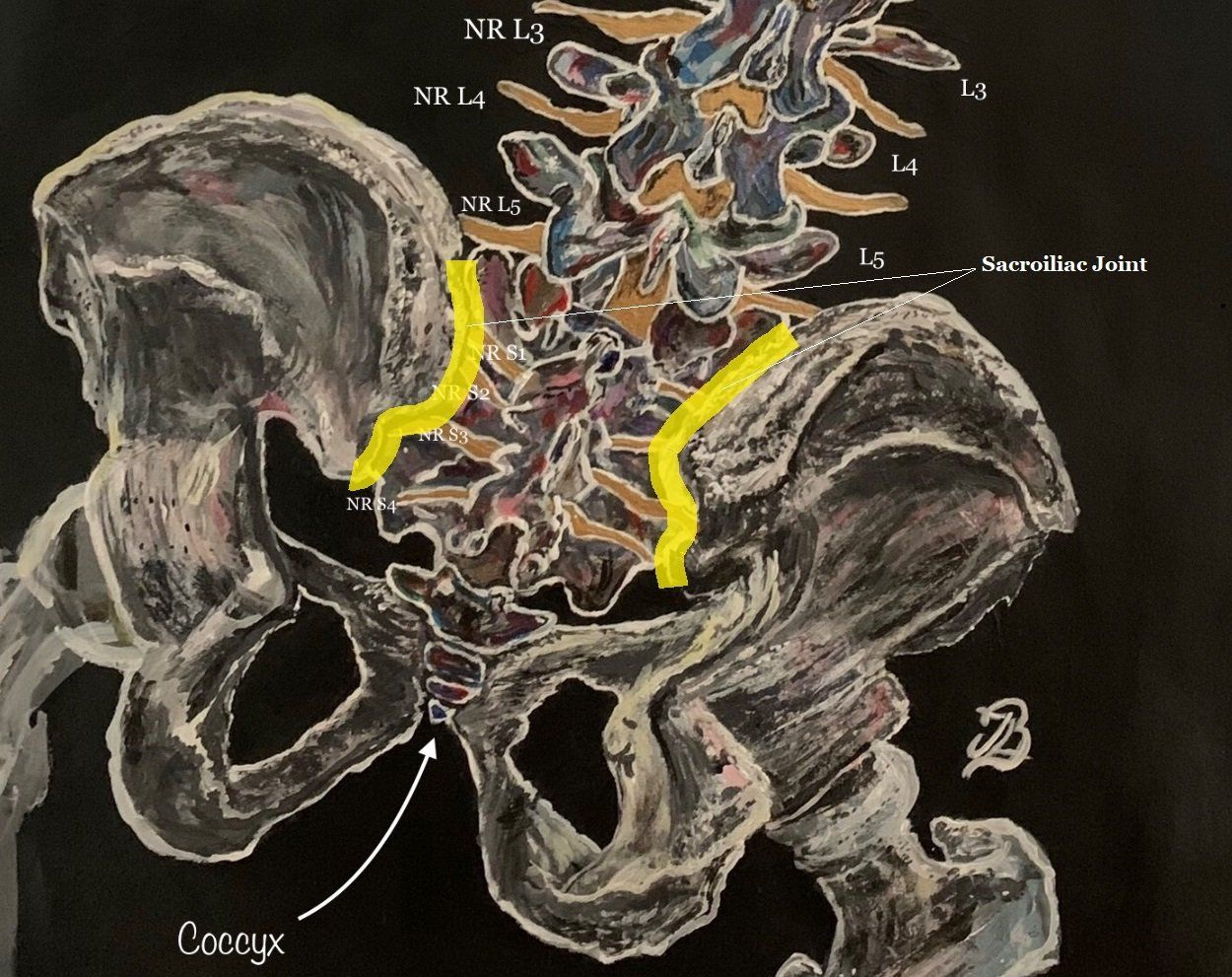

The sacroiliac joint consists of articular surfaces; the sacrum and iliac bones (figure 2). The sacrum is a large triangular bone situated at the base of the vertebral column and comprises of five fused vertebrae wedged between the two iliac bones. Iliac nerves exit the foramen anteriorly and posteriorly (figure 2).

The primary purpose of the SIJ is to maintain stability which is achieved by the union of the iliac ridge surface which 'sits' on the depressed sacral surface (6). The joint's movement is also minimised via the dense ligamentous network and surrounding muscle attachments which guide movement and enhance the stability to the pelvic bones (6).

Interesting Biomechanics of the SIJt

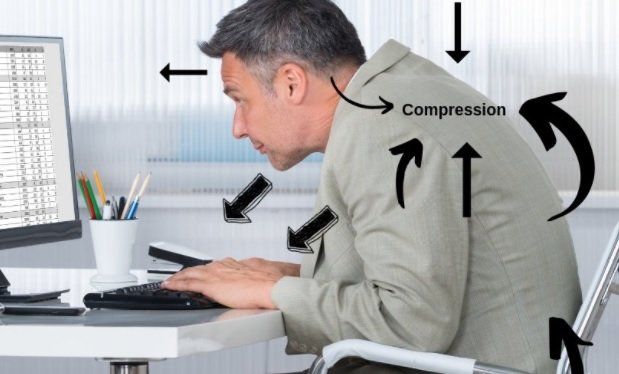

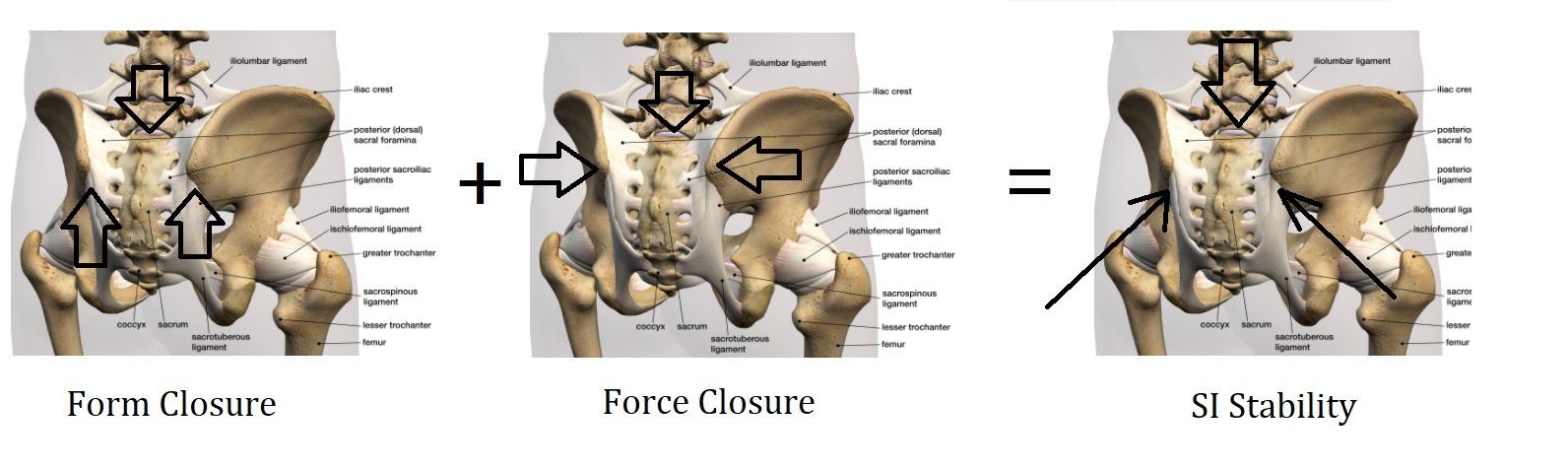

Limited movement of the sacroiliac joint has been explained by the theory of form and force closure which establishes stability in the sacroiliac joint. A combination of the pelvic anatomy, ligamentous and muscular forces help 'lock' the joint and prevent movement.

Form Closure refers to stability provided by the overall structural boney shape of the sacroiliac joint with relation to the surrounding tissues such as the capsule and ligaments and is derived by the triangular shape of the sacrum which allows the bone to fit neatly between the innominates (or ilia) ‘like a keystone in a Roman arch’ (12).

The surrounding ligaments (namely the sacrotuberous and sacrospinalis) help aid stability and minimise shearing of the SI joint. Ageing increases joint friction and helps the formation of interlocking ridges. The roughening of joint surfaces help the joints to 'lock' better together (12). The theory indicates that some individual's SI joints are more naturally stable than others', as their overall shape helps withstand certain forces.

Force Closure

Refers to surrounding tissue structures that hold the SI joint together and include the muscles and ligaments that cross the area of the SI joint and the thoracolumbar fascia (a big sheet of connective tissue that supports the lower back).

Force closure also arises from the contraction of the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ myofascial units, or ‘core’ muscles which help to stabilise the pelvis, lumbar spine and hip joints or ‘lumbo-pelvic-hip complex' (12). Force closure of the SI joints may reduce and suffer as a result of problems such as (12):

1. Muscle weakness or atrophy.

2. Inadequate recruitment of muscles during movement, which can also result in muscle weakness.

3. Uncoordinated contraction and relaxation of muscle systems, resulting in failure to provide adequate stability and a consistent control of motion (12).

Compensatory movement patterns that a patient might start to use can cause muscle imbalances and weakness. Impaired muscle tension and control can result to abnormal stresses on the musculoskeletal system and may lead to eventual overuse and further imbalance of certain muscle groups surrounding the lower back, buttocks and knees (12).

Overall, adequate combination of force and form closure helps provide stability and strength for the SI joint. It could be theorised that pain occurs when either one of these mechanisms might be disturbed (figure 3).

Presentation and Pain Patterns

Diagnosing and treating SIJ dysfunction can be challenging with its inconsistent presentation, however, the most consistent factor for identifying SIJ pain is unilateral pain below the fifth lumbar vertebra or 'L5' (6).

SIJ commonly presents with localised referred pain including(6):

· Lower buttock pain, which is as common as 94% of all cases (6).

·Lower lumbar region pain (72%).

·Lower extremity (50%)

·Leg pain

·Groin and inner thigh pain (14%)

·Hip pain

·Muscle spasms, with the most common muscle groups involving the hamstrings, hip flexors and quadriceps (6).

Symptoms can be described as dull and achy to sharp and stabbing sensations and aggravating factors may include all types of physical activity such as bending, climbing, lifting and rising from a chair or car (6).

Causes of SIJt Pain

Biomechanical Adaptations

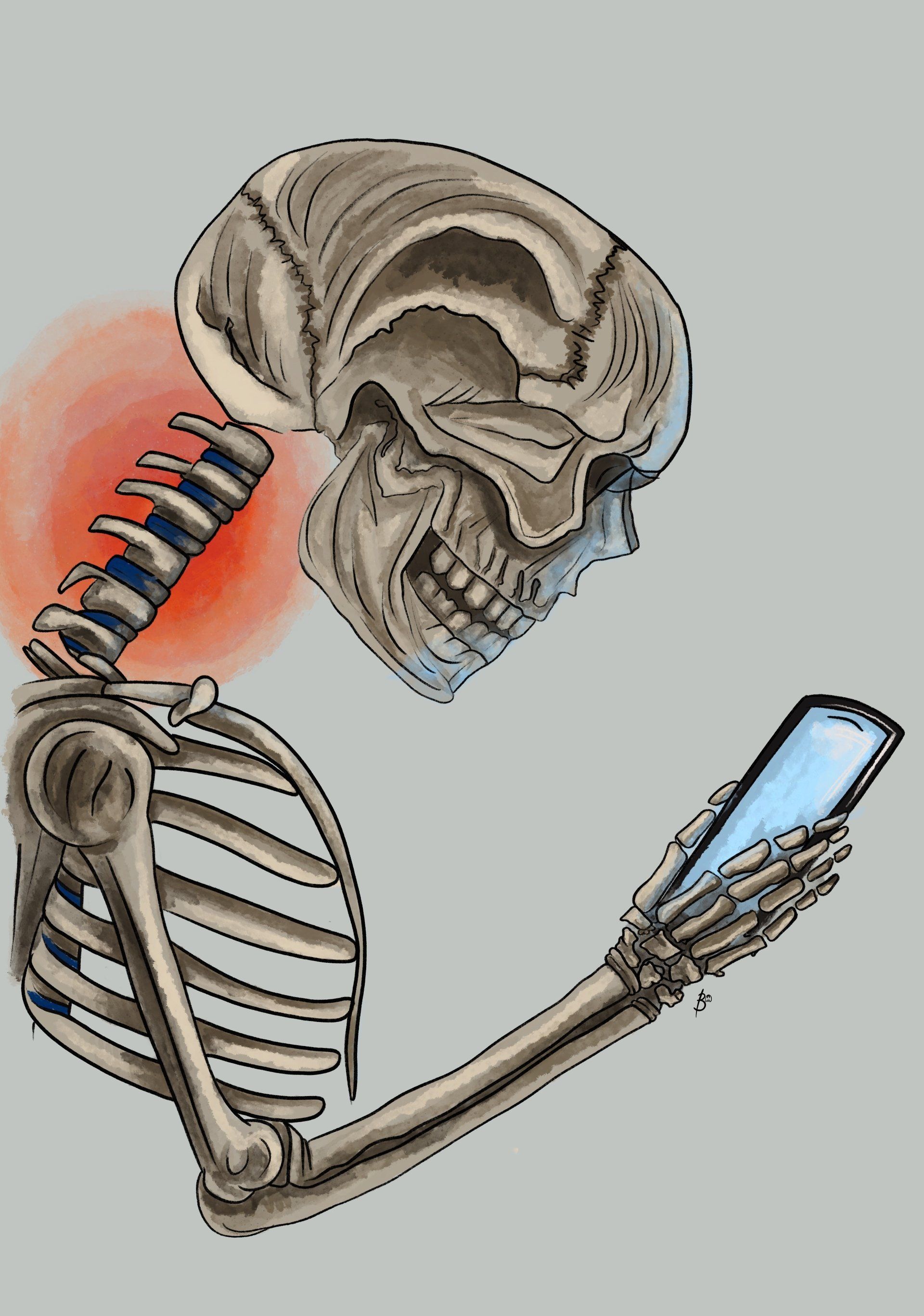

As a protective mechanism, the brain will make the body compensate and adapt whilst we regularly perform our day-to-day bodily movements, such as walking and sitting, long after an initial injury to help avoid further injury. People who present themselves with sacroiliac joint pain often report that the pain came on gradually and that there was no memorable incident or 'sudden onset'.

Altered movements and compensations that lead to a gradual, slower increase in intensity of symptoms is otherwise termed as an "insidious onset" (1). This means that The biomechanical adaptations can lead to muscle imbalances by becoming either overactive and hypertonic or underactive and hypotonic which can lead to muscle group tightness and weakness.

Trauma

Sacroiliac joint pain can be as a result to acute trauma from activities such as heavy or prolonged lifting and bending, repetitive torsional (rotational) strain, a fall onto the buttocks or a rear-end motor vehicle accident.

Overuse

Chronic repetitive shear or torsional (rotational) forces may also result to sacroiliac joint dysfunction with participating in activities such as performing the golf swing, throwing sports such as baseball, tennis, bowling, constant sitting or lying on the affected side.

Other Causes

Injury to any of the surrounding structures of the SIJ can be a source of pain. Other causes may include (2):

- Arthritis.

- Spondyloarthropathies (e.g.ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and enteropathic arthritis (EnA)).

- Ankylosing spondylitis (AS): an inflammatory rheumatic disease that involves the spine and SI joint and manifests as spondylitis and sacroiliitis (3).

- Leg length discrepancy; anatomic leg length discrepancies should be determined as early in treatment as possible so that the appropriate modifications can be accomplished (11).

- Lumbosacral transitional

vertebrae (LSTV).

- Gait and biomechanical abnormalities.

- Persistent strain/ low grade trauma (e.g. jogging)

- Scoliosis.

- Pregnancy - one sided weight bearing, exaggerated lordotic posture,third-trimester hormone-induced ligamentous relaxation, pelvic trauma associated to parturition (2).

- Spinal surgery.

Treatment Options

Overall, there is no

gold standard for treatment, leaving clinicians to use

their experience in making recommendations (11).

Acute Phase (1–3 Days)

Often, SIJ pain presents as a progressive problem with fluctuations in symptoms. Thus, acute injuries are often associated with a direct trauma such as a fall or increased frequency or intensity from performing a from a specific activity. The patient may experience symptoms only during certain activities, including sports or exercise.

During the acute phase

, anti-inflammatory medications and icing arehelpful. Relative rest after an acute injury assists with

pain control. This includes restricting running or excessive walking, as these activities often provoke SIJ pain.

Identifying the activity that may aggravate symptoms is

important, especially in those with progressive onset of

symptoms. In general, avoiding activities that require

single leg stance activities such as bowling, skating, running,

and stair-stepping would be helpful to alleviate symptoms.

Correcting asymmetries in muscle length or stiffness

should start as soon as possible and performed pain free.

How Might Osteopathy Help?

Hands-on treatment techniques including mobilisation of the SIJ can be quite helpful in restoring

function along with articulation, manipulation or mobilisation of neighbouring joints; muscle energy and active

release therapy (11). Treatment of patients with significant muscle

weakness, poor endurance, or both may need to focus on

stabilisation through strengthening of muscles. Special care should be taken with early

treatment of the pregnant patient, as aggressive stretching or mobilization can further aggravate symptoms secondary to pregnancy-related joint hypermobility (11).

Recovery Phase (3 Days to 8 Weeks)

When pain levels are manageable, biomechanical deficits or studying compensatory movement patterns become the focus of rehabilitation to further understand tissue overload complexities. Muscles that are commonly found to

be shortened (or tightened) include the front and inner thigh muscles (i.e. rectus femoris,

tensor fascia lata, hip adductors), lower back, outer abdominal and deep buttock muscles (i.e. quadratus lumborum,

piriformis, obturator internus, and latissimus dorsi).

Particular attention is given to the piriformis muscle's length, continued inflexibility of this muscle is often

thought to be part of the source of recurrent pain.

Muscles that are commonly found to be weakened with chronic sacroiliac joint pain include the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, lower abdominals, and hamstrings. Exercise prescription from the manual therapist are given throughout the course of treatment to help reduce the muscle length or tension.

Sacroiliac Joint Belts

can be used to provide compression and thereby proprioceptive feedback to the gluteal

muscles. Vleeming et al6 reported that SIJ belts applied

to cadaver models reduced SIJ rotation by 30%. Clinically, it makes sense that SIJ belts can be especially

helpful in patients with SIJ hypermobility or significant

muscle weakness. Care must be taken to insure that the

patient is able to apply the belt appropriately. The SIJ

belt should be secured posteriorly across the sacral base

and anteriorly, inferior to the anterior superior iliac

spines. Patients are usually instructed to wear the belt

during walking and standing activities. However, patients with significant pain and weakness often find the belt helpful in reducing symptoms when worn during

sedentary activities as well.

Orthotics and

shoe modifications

.

A shoe lift to correct a functional leg

length discrepancy can be helpful during the acute stage to

manage pain but should be approached with caution, as functional leg

length discrepancy should be corrected with muscle rebalancing and not orthotic intervention (11). An inappropriate

shoe lift can promote adaptive muscle imbalances, which

may initially be asymptomatic but can cause problems

later because of a shift in force transmission. Anatomic

leg length discrepancies should be determined as early in

treatment as possible so that the appropriate modifications can be accomplished.

Cortisone and Nerve Block Injections

Sacroiliac joint injections might be considered for if the patient’s progress plateaus or if the physical therapy program cannot be advanced because of pain

provocation. Injections can also be used diagnostically if performed under fluoroscopic guidance (11).

Surgery Considerations and Fixation

Special consideration should be given to individuals with joint hypermobility. SIJ arthrodesis and percutaneous joint fixation has been used for instability (11).

However, long-term

outcome studies suggest that it

is unknown what happens to surrounding articulations

such as the lumbar spine, contralateral SIJ, and hip long

after an SIJ fusion.

References

1.) Clayton, P. (2016) Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction and Piriformis Syndrome The Complete Guide for Physical Therapists, Lotus Publishing, Chichester England.

2.) Cohen, S. P., Chen, Y., Neufeld, N. J., (2013) Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment, Expert Reviews Ltd, 13; 1: 99–116.

3.) Cohen, S., P. (2005) Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Comprehensive Review of Anatomy, Diagnosis and Treatment, Anesth Analg, 101: 1440-53.

5.) Ha K, Lee J, Kim K (2008) Degeneration of sacroiliac joint

after instrumented lumbar or lumbosacral fusion. Spine 33:1192–1198.

6.) Hamidi-Ravari, B., Tafazoli, S., Chen, H., Perret. (2014) Diagnosis and Current Treatments for Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction: A Review, Current Physical Medical Rehabilitation, Springer Science and Business Media New York; 2: 48-54.

7.) Hansen, H. C., Helm, S. (2003) Sacroiliac Joint Pain and Dysfunction, Pain Physician; 6: 179-189.

8.) Ivanov AA, Kiapour A, Ebraheim NA, Goel V. Lumbar fusion leads to increases in angular motion and stress across sacroiliac joint: a finite element study. Spine 34(5), 162–169 (2009).

9.) Kibsgard, T. J., Rohrl, S. M., Rosie, O., Sturesson, B., Stuge, B. (2017)

Movement of the sacroiliac joint during the Active Straight Leg Raise test in

patients with long-lasting severe sacroiliac joint pain, Clinical Biomechanics; 47: 40-45.

11.) Prather, H. (2003) Sacroiliac Joint Pain: Practical Management,Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc., Philadelphia; 13: 252–255.

12.) Sahin, O., Harman, A., Akgun, R. C., Tuncay, I. C. (2012) An Intraarticular Sacroiliac Steroid Injection Under the Guidance of Computed Tomography for Relieving Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Clinical Outcome Study with Two Years of Follow Up, Turk Rheumatol, 27; 3: 165-173.

13.) Schamberger, W. (2012) The Malignment Syndrome: Diagnosing and Treating A Common Cause of Acute and Chronic Pelvic, Leg and Back Pain, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

14.) Slipman, C. W., Sterenfeld, E. B., Chou, L. H., Herzog, R., Vrestilovic, E. (1998) The Predictive Value of Provocative Sacroiliac Joint Stress Maneuvers in the Diagnosis of Sacroiliac Joint Syndrome,

15.) Snijders, C. J., Hermans, P. F. G., Niesing, R., Spoor, C. W., Stoeckart, R. (2004) The Influence of Slouching and Lumbar Support on Iliolumbar Ligaments, Intervertebral Discs and Sacroiliac Joints, Clinical Biomechanics.

16.) Szadek, K. M., van der Wurff, P., van Tulder. M. W., Zuurmond, W. W., Perez. R. S. (2009) Diagnostic Validity of Criteria for Sacroiliac Joint Pain: a Systematic Review,The Journal of Pain, 10; 4: 354-368.

17.) Yoshihara, H. (2012) Sacroiliac Joint Pain After lumbar/ lumbosacral Fusion: Current Knowledge, Eur Spine J, Springer-Verlag, 21: 1788-1796.